‘Mad One’ is based on a quote from Jack Kerouac:

"The only people for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars…" —Jack Kerouac, On the Road

I use “Mad One” as an empowering term to mean those who use creativity and have mental health experience, without using diagnostic labels.

“Maybe nobody is crazy, but we are all just a little bit MAD. How much depends on how lucky you are.”

“I had a choice to deny my ‘mental illness’ and embrace my ‘Mental Skillness.’”

—Joshua Walters, from a TED Talk, “On Being Crazy Enough,” 2011

I use labels like, “Mad One” and “Mental Skillness” to define myself.

My reason for becoming a TED Speaker had to do with my diagnostic label “bipolar.” I was diagnosed with that label when I was 16. When I was 31, I was told I was schizophrenic and then schizoaffective. I never received an explanation from a doctor on why my diagnosis was changed. This change ultimately made me not believe in mental health diagnoses.

When a doctor gives you a diagnosis, it is one person's opinion. You don’t have to agree with it. But because that diagnosis comes from the medical profession, it goes in your record and stays with you forever. So, it’s up to you whether you agree with it or not. It’s up to you to share it with others or make it publicly known.

Another instance of labeling is when you get picked up by the police. It goes on your permanent record. Whatever that policeman writes down in his report as your charges endure. Not only what you are convicted of, but these initial reports of what they take you in for, stay with you for the rest of your life. Your history can be traced by your legal name, your birthdate, and your fingerprints.

Whenever I apply for a job that then asks for fingerprints, I don’t apply. I know they are going to see all of my four charges.

One charge I have is theft, even though I was picked up in my place, in my room, in my underwear. What was I stealing? I had broken things. But I broke them in my place.

Your word doesn’t mean anything against the police’s word. You're just a guy in his underwear screaming. Your roommate called the cops because he didn’t know you had a mental health condition. If I was a person of color or in a different state, the police might have shot me.

What’s the difference between mental illness and criminality? No one ever explained that to me. If someone commits a crime, are they a bad person? Or do they have a mental illness? Why don’t we get rid of prisons and rehabilitate people in hospitals with trained professionals?

I know firsthand the difference between such hospitals and jail. I have a dozen experiences in mental hospitals: in Pennsylvania, Canada, France, and California. I think I’ve been to most of the institutions in the Bay Area: San Francisco, Oakland, San Jose, Fremont, Novato, Santa Clara, Palo Alto, San Leandro, and Berkeley. Part of being in and out of the hospital is that when you are free, you try hard not to go back in…and there was a period when I kept going back in.

And then I went to jail, for the same mental setbacks I went to the hospital for: acting strange, acting erratic, hallucinating. The experience of jail was much different than the hospital experience.

When the police picked me up in Petaluma, I didn’t know there were charges out for my arrest from a previous hospitalization. One cop was certain I didn’t need to go in. What crime was I committing? I was talking loud. Is that a crime? Being a public disturbance? The two cops disagreed in front of me.

On the ride to Santa Rosa in the back of the cop car, I was thinking, I’ve been to so many hospitals, I wonder who I’ll meet in jail? There's a little room they hold you in for processing. There was a phone, but you could only dial a number with the local area code. The guard said my bail was $500. I could have just paid it and walked out, but I didn’t know how the system worked.

I was so far gone, the guy in the next cell was mumbling and I thought his voice was inside my head. I didn’t know where I was or what was happening to me. And then, when they locked me away, I realized: Oh, this is jail, this is not the hospital. There is a little call box you can use. I called and said, “There's been a mistake, I’m supposed to be in the hospital, I have a condition.” I gave them my Kaiser number, but once you're in jail, you're in. You're not going to say anything that gets you out. The first time they let me out in the courtyard, there were three other guys there. I heard them talking about “D Block.” About how our block was the best. It started to sink where I was: jail! I started to cry. They really couldn’t handle that. Back in my cell, I used the call box again. I kept screaming so that they moved me to a different part of the jail—the part for mental illness. Now they would come around a give us outdated medications along with horrible food.

Some people asked to talk with me, but I wasn’t trusting anyone. People in this new wing of the jail were very disturbed. Unable to take care of themselves. Rage. Gang members. We got 45 minutes outside of the cell each day. We went to the courtyard. I was so angry at God for putting me here. I used my voice to rehearse my show. It was the best performance I had ever given. There was only one other human within earshot on the other side of the wall. I did my story, I did my poems, I sang Raggea….”Ethiopia to Father's Land, Closer to God we Africans…”

I was rehearsing, I was going to perform when I got out. I was going to make it big.

There was a guy in there, David. He had been in jail for 15 years. He said, “You rap nice, but we want a book.” This book is for him.

I used my time outside my cell to speak. The Raiders were moving to Las Vegas. “Fuck the Raiders!” I said. “All the murders that have happened in the Colosseum parking lot. Good Riddance.”

I called my mom. There was an older inmate in the next cell who asked who I had just called, and I told her. “I wish I could call my mom,” she said. That put it in perspective: I still had parents to call.

I called Uncle Jack. He always has something funny to say:

My Montreal hospitalization, 2012: “Is this a good career move?”

When I broke my ankle, 2023: “Does this mean your bowling career is over?”

In jail, he wanted to know: “Is this the only time you're going in there…?”

He sent me some papers with printed-out documents on how to get a lawyer through the mental health system. I read it and then used the back of the pages to write my book.

I got a pencil stub from the guard and turned the pages around to start my life story.

I started with a Yelp review of every hospital I had ever been in—eight hospitals up to that point. I gave them all a review. My honest critique.

I also wrote down my dreams. I had been keeping a dream journal for seven years. I had dreams about people I knew. The strange thing about dreaming in jail is your reality is a nightmare, so any dream you have is a relief.

I kept those pages, I still have them. When I first entered my cell, I thought of all my heroes who had been jailed. Nelson Mandela, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr. I thought about how they had written during their incarceration. They had read everything they could get their hands on. They had built their legacy during that jail time, and when they got out they rose to prominence.

For them, jail wasn’t being thrown away or forgotten. It wasn’t death, and it wasn’t a time to rot and hate themselves. It was a time to build their base, write, connect, and plan their next moves.

To be in isolation, to spend 23 and a half hours alone, is to be a monk and find out what's important. Some guys work out, while other guys scream. There were many moments when I lost my sanity, but there was no one there to comfort me. I had to rebuild the wall of my psyche from my cell. I kept falling apart and rebuilding without the help of doctors or medication.

The first moment inside was the lowest. I felt like a failure. Like my life was ruined. Like I was a disgrace to my family and everyone I knew. That I wanted to die. I wanted to put my head in my plastic jail pillow and disappear. I wished I had never been born.

I went to trial within a couple of weeks, and I could barely sit on the stand. They have you dressed in orange and you have to hop down a long tube with your chains on. It was exhilarating to be so far out of the cell. That long tube I imagined was walking to the taping of my comedy special, dressed in prison orange. The crowd was waiting, the cameras rolling, and I was ready to perform.

When my trial began, I cried. I wasn’t meant for this. I couldn’t hold it in. I was seated with four other guys who were also on trial. My emotions made them uncomfortable. At the second trial, two weeks later, my parents were there. The judge told me to stay on my medications and stay away from where I was arrested. They let me go. I was only in jail for a month. The longest month I had ever experienced.

The day they let me go, I waited five hours for my release, the longest hours I had ever experienced. My parents were waiting for me. Finally, out, we went to find my car—still on the street where I had left it, and no ticket. I drove to my parents’ place, to try and rebuild.

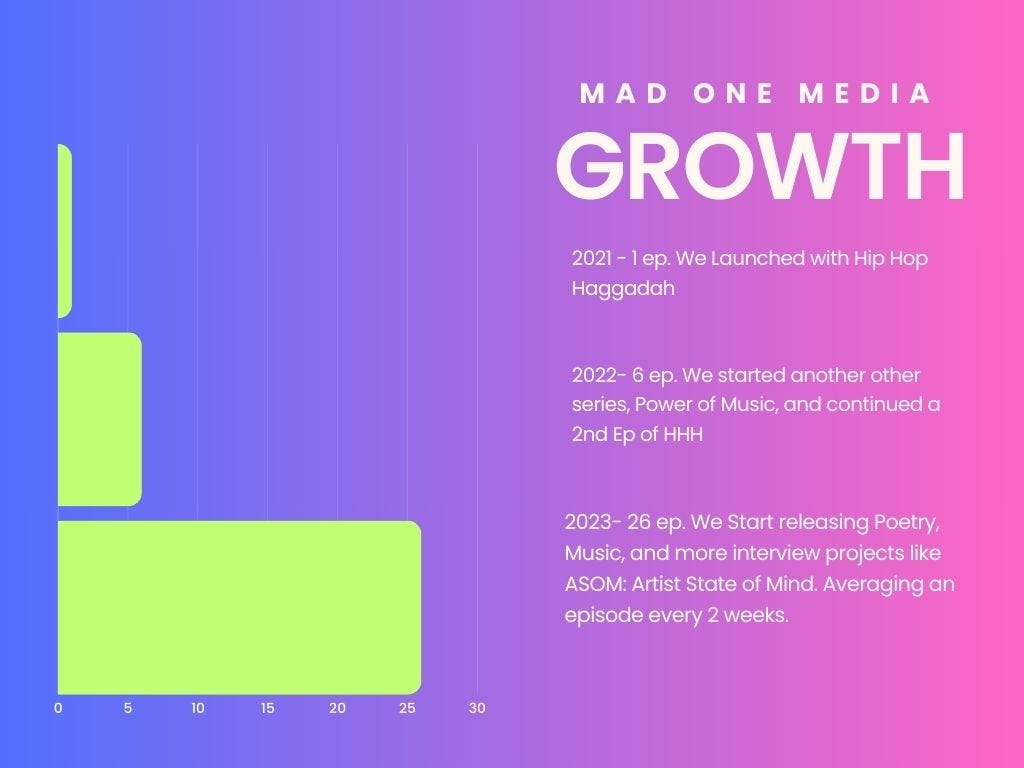

Growing our Platform and Label we have expanded our Offerings every year and grown our platform to include more audio and written work. After 3 years the growth continues. Support below by becoming a subscriber.

Riveting. More, please!